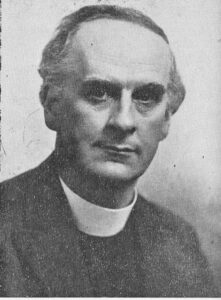

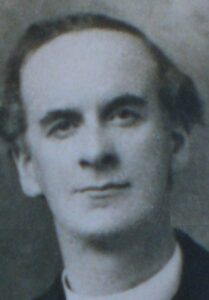

When my first book was published back in 2006, Dad told me about my great grandfather Edward Tegla Davies, who was a Methodist minister and children’s author. Dad showed me an old copy of Nedw, one of Tegla’s best known works. Nedw in Welsh is short for Edward and is pronounced Ned-oo. The language is natural (according to Lionel Madden, author of Methodism in Wales, Tegla ‘wrote as children spoke’) and the style is gentle and wry – very different from the rather severe religious stories commonly offered to children at the time.

Nedw was illustrated by Leslie Illingworth, who was political cartoonist for the Daily Mail and contributed to Punch and other magazines.

Tegla made quite a splash on the Welsh literary scene, writing for adults as well as children. He has a brief wikipedia page in English (Edward Tegla Davies) and a fuller one in Welsh (Edward Tegla Davies). There is also a long entry on the website Welsh Biography Online, which includes this gem:

Tegla regarded himself as a rebel all his life. Although he was one of the most prominent preachers and one of the most influential men of his denomination, he did not refrain from criticising and satirising organizational systems, whether religious or secular.

Dad recalls that his grandfather was kind and gentle, that he always wore his clergyman’s collar (even on the beach!) and that he had various stock party tricks to amuse the grandchildren. On country walks he used to collect acorns, turn them upside-down and draw faces on them, so that the acorn’s cup resembled a hat. Tegla possessed the rare gift of having stayed in touch with his inner ten year-old, a gift that equipped him well for his children’s writing.

Edward Davies (pronounced Davis) assumed the name Tegla when he was ordained as a Methodist minister – there was already an Edward Davies in the ranks and he needed a distinct appellation. He took the name Tegla from the name of his birthplace Llantegla (lit. Church of Thecla) in north Wales. Saint Thecla was a first-century saint about whom various apocryphal stories are told. The name stayed in the family for two generations – my grandfather and father were both given it as their middle name, but I was not.

At the age of 14, Edward Davies was a pupil-teacher at Bwlch-gwyn school in north Wales. Promising pupils who completed primary school would sometimes be asked to stay on as teachers – classroom assistants, most likely – and this is what Edward did. He was greatly influenced by a young teacher there called Tom Arfor (pronounced Ar-vor) Davies, who ‘awoke his interest in the history and literature of Wales’ (citation). Dad tells me that the Edward was present when his teacher started coughing up blood, and that he died shortly afterwards. It was in memory of Tom Arfor that Edward later named his own son (my grandfather) Arfor. But the legacy of Tom Arfor was more than a name. A passion for reading and writing had been stoked in the young teenager.

From his reading of the Welsh classics, Edward acquired ‘a Welsh prose style of great purity and naturalness’ and ‘although he never had a Welsh lesson at school nor went to university, he became one of the most prolific writers in Welsh.’ (quotation from Rev. Dr Islwyn Ffowc Elis, Welsh Biography Online).

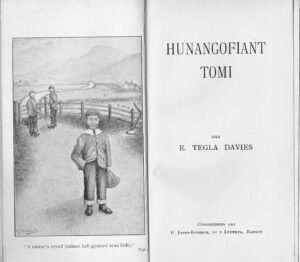

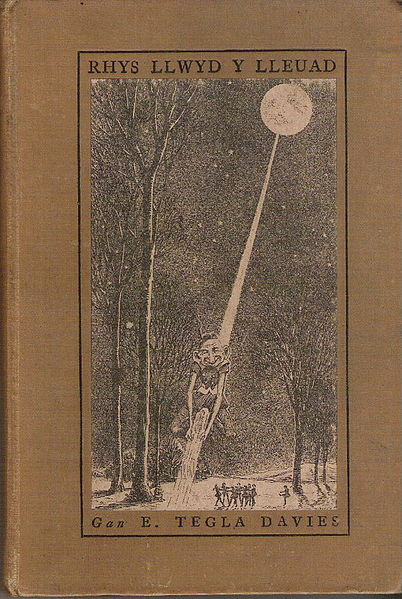

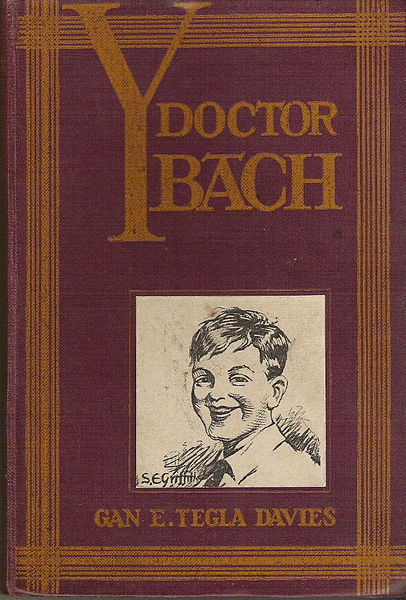

Edward (often called by his middle name ‘Tegla’) contributed boys stories to a Welsh language magazine called Y Winllan (The Vineyard), of which he became the editor. The stories were eventually published as books in their own right. The first to be released was Hunangofiant Tomi (Tomi’s Life, 1912), the fictional diary of a country boy in north Wales. It was gentle and wry in tone, documenting Tomi’s various adventures and scrapes. There followed Nedw (Ned, 1922), Rhys Llwyd y lleuad (Rhys Llwyd the Moon, 1925), and Y Doctor Bach (The Little Doctor, 1930).

According to the Welsh literary critic Meic Stephens, Tegla’s boy heroes were ‘mischevious, dreamy and tricksy’ (citation). In the story Do Zebras, for example, a boy called Birch and his friend Humphrey paint a donkey to look like a zebra. Tegla’s characters remind me of William and the Outlaws (Ginger, Henry and Douglas) from Richmal Crompton’s much-loved William series. In 1922, the same year as Do Zebras was published in Bangor, the first William book Just William was being published in London. And by strange coincidence, chapter five contains a scene in which William paints Henry’s dog blue as a circus exhibit.

“Blue dog,” said the showman, walking forward proudly and stumbling violently over the cords of the dressing gown. “Blue dog,” he repeated, recovering his balance and removing the tinsel crown from his nose to his brow. “You never saw a blue dog before, did you? No, and you aren’t likely to see one again, neither. It was made blue special for this show. It’s the only blue dog in the world. Folks’ll be comin’ from all over the world to see this blue dog—an’ thrown in in a penny show! If it was in the Zoo you’d have to pay a shilling to see it, I bet. It’s—it’s jus’ luck for you it’s here. I guess the folks at the Zoo wish they’d got it. Tain’t many shows have blue dogs. Brown an’ black an’ white—but not blue. Why, folks pay money jus’ to see shows of ornery dogs—so you’re jus’ lucky to see a blue dog an’ a dead bear from Russia an’ a giant, an’ a wild cat, an’ a China rat for jus’ one penny.”

Just William, chapter 5, Project Gutenburg

Rhys Llwyd the Moon is a collection of stories about a small moon (!) and the adventures it/he has with a couple of boys in rural Wales. The word surreal is often used when writing about Tegla’s books, and you can see why. The book’s popularity was helped by the fact that it contained six black and white illustrations by the popular children’s book illustrator and landscape artist William Mitford Davies.

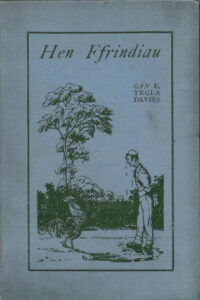

The Davies & Davies author/illustrator team also produced Hen Ffrindiau (Old Friends, 1927). The old friends alluded to in the title are Welsh folk tales, popular rhymes and proverbs. Here you will find witty anecdotes about the red-faced cobbler of Rhuddlan, the yellow foal, the mountain chicken and other absurdities. This is a real classic – a book for children of all ages, including adults. I dearly wish that there existed an English translation of this one. This was the first of several fantasy novels by Tegla, including a book of Welsh fairy tales Tir y Dyneddon (Dyneddon Land, 1921) and Stori Sam (The Story of Sam, 1938 ).

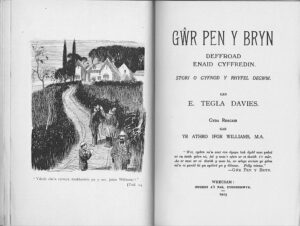

Tegla also wrote a novel for adults. Gwr Pen y Bryn (The Master of Pen y Bryn, 1923) was serialized in the periodical Yr Eurgrawn (translation, anyone?) before appearing in book form. It is Tegla’s only novel that was translated into English. It has as its background the Tithe War of the 1880’s and describes the Christian conversion of a rich farmer called John Williams. Emeritus Professor Robert Maynard Jones (1929-) called it ‘one of the most impressive novels of his time’ (citation). Lionel Madden related how the book was described “with pardonable exaggeration” as “the greatest Welsh novel”.

But the novel also had its detractors. It was decried by one leading critic on the grounds that Tegla had insisted on ‘saving’ his central character. ‘Whatever its shortcomings,’ wrote novelist Islwyn Ffowc Elis, ‘The Master of Pen y Bryn is a milestone in the history of the Welsh novel because of its ordered plot and its penetrating study of a soul in anguish.’

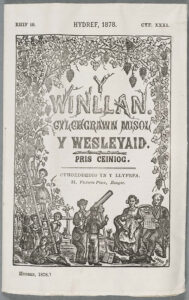

Y Winllan (The Vineyard) was a Wesleyan magazine for children, published monthly in Welsh. Edward Tegla Davies started off as a reader of Y Winllan, then became a contributor and finally became its editor.

In 1878 the copy you see here was placed inside a glass bottle and hidden behind one of the foundation stones of a new Welsh Wesleyan Chapel in Aberystwyth. The chapel closed in 1992 and the bottle was discovered in 1999 whilst work was being undertaken to convert the building into a tavern.

Edward Tegla Davies was in his mid-twenties during the Welsh Revival, a period of explosive church growth in Wales in 1904-5 that sparked a Christian ‘awakening’ in many other countries. During that time, taverns were going bankrupt and churches were full to bursting. According to the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, Tegla had a conversion experience after attending a preaching festival at Coedpoeth, and decided to enter the ministry. In the course of his life he ministered in Abergele, Leeds, Menai Bridge, Port Dinorwic, Tregarth (thrice), Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant, Denbigh, Manchester (twice), Liverpool, Bangor and Coedpoeth.

Lionel Madden writes:

Tegla was not a natural preacher, but he laboured to make himself effective. Here he describes his early efforts.

I was born into the tradition that you were not a preacher unless you were a ‘tuner’ (one who employs sing-song cadence in the delivery of a sermon). I would do my best, making myself terribly hoarse and leaving me with a very sore throat on a Monday morning. I was envious of those tuners who could provoke tears, for the proof of a successful service in those days was that the congregation was in floods of tears. The only tears I could conjure up were tears of compassion for my raucous attempts.

He moderated his preaching style, adopting a more conversational approach, but never quite lost the sense of strain. There were, however, other features that more than compensated for this and propelled him into acceptance throughout Wales as one of the leading preachers of his day. He was a master of apposite illustration and of clear exposition. His idealism ran alongside a fiercely critical mind, and the boldness with which he advanced one or the other made what he said perpetually challenging. Above all he appeared to be a prophet for his time.

Tegla did not prize preaching for its own sake, and his tone was wry when he wrote about the ‘tuners’ and the ‘two-sermon-a-night’ preaching meetings. He was more interested in ongoing discipleship, and for this the home setting was more significant than the church.

I am firmly of the opinion that the smallest contribution to the spiritual life of the Church in my time has been preaching at preaching meetings. I am convinced that the chief reason for our intellectual and spiritual poverty, and our lack of influence in the world, is that we have failed to educate our children, young people and all ages, in the basic principles of our faith.

It is no surprise, then, that many of Tegla’s stories for young people touch on spirituality. One of the tales in the collection Hen Ffrindiau (Old Friends, 1927) was called Samuel Jones the Hendre. Here are the bare bones of the story:

There were two farmers at harvest time: Samuel Jones the Hendre and Mr Herbert Fron. Samuel Jones’ land was very poor compared to Mr Herbert Fron’s fertile and copious land. When it was decided to decorate the chapel for the Thanksgiving Service, most of the fruit and vegetables came from Mr Herbert Fron’s fields and green houses. Samuel Jones was not at all happy about this, as he could only offer thorns and brambles. Shortly before the service began, Samuel Jones crept into the church and slyly exchanged Mr Herbert Fron’s abundant crops for his own thorns and brambles. The outcome was that everyone refused to participate in the service. They said that it was impossible to thank God in the middle of thorns and brambles. Everyone refused, except for one, and that was Samuel Jones himself. He had remembered a verse from Isaiah 66 – “Has not my hand made all these things?” – and he worshipped happily alone, surrounded by his thorns and brambles.

Another of Tegla’s works for children tells the story of the Holy Grail. In the post Davinci Code era we tend to think of Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland as the final resting place of the Grail, but medieval specialist Dr Juliette Wood believes that Wales has a much stronger thread of grail legends. In March 2013, Dr Wood delivered a lecture at the Museum of London entitled The Phantom Cup that Comes and Goes, giving evidence for the Welsh claim and making reference to Tegla’s work:

Edward Tegla Davies (1880-1967), a well-known Wesleyan Methodist minister, produced a charming curiosity called Y Greal Sanctaidd. This booklet for young readers traced the history of the grail legend with the emphasis on its relevance for Wales. Tegla summarized the medieval grail texts, pointed out parallels with early ‘pagan’ Welsh literature, such as Ceridwen’s cauldron, and presented a short exposition on how modern writers, among them Alfred Lord Tennyson, used the motif in their work. The focus was on the spiritual meaning of the grail and its continued relevance to Welsh life, but the distinctiveness of Tegla’s book lies in the fact that it is aimed at a young audience.

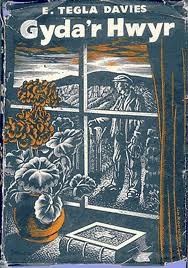

None of my great-grandfather’s works for children are available free online in translation. All I could find in English is the adult essay That Grave from his book Gyda’r Hwyr (At Dusk, 1957). The essay is his account of a country walk with a friend to visit Cardinal Newman’s grave. I was thrilled to find this because it gives real insight into Tegla’s spirituality, his love of nature and his keen critical sense. The whole essay is worth a read, but here are three extracts which I found particularly interesting.

First, Tegla’s thoughts on the fine line between faith and superstition. The passage demonstrates his love of animals and his flair for asking interesting questions.

After going some two or three hundred yards on this get‑away‑from‑it‑all pathway we turned to the left. On one side of the turn is an old shed and on the turn, on a small rise, there is a cross and inscribed on it are the following words:

LAUS DEO. In thankful remembrance of June 30th, 1866, when Divine Providence saved our schoolboys all collected round their father prefect under the adjacent shed, from a sudden thunderstorm when the lightning playing around them struck with death as many as ten sheep about the field and trees close by.

It would perhaps be uncharitable to suggest that as Providence had saved the boys and the prefect it should also have thrown its covering over the poor sheep as well, especially as the ruler of Providence is the author of the parable of the Lost Sheep. By praising Providence in this way does not this testimony also diminish it by making it seem rather miserly in its defensive operations? The line between superstition and faith is a fine one and is quite characteristic of the faith that put up this stone.

And this on the Catholic Church:

There is something hellish in the Catholic Church and there is something heavenly too. It was she who created Catherine de Medici and her followers, whose likes not even Gehenna could have imagined. And it was also she who created Francis of Assisi and his ‘friars’, and not even Paradise could have devised more lovely lives than theirs.

And this, when finally he and his friend arrive at Cardinal Newman’s grave:

We just stand there, not uttering a word, and we stare for a long time, spellbound, and the eloquent simplicity is the most spellbinding thing of all.

Tegla considered himself a rebel all his life, and ended up declining an OBE in 1963, four years before his death. I asked Dad why his grandfather declined the OBE and he responded that ‘although Tegla was never a Welsh nationalist, he was a patriot, and may not have fancied being honoured by the English monarchy.’ That said, he was not the only writer to decline an MBE, OBE or knighthood. CS Lewis, Roald Dahl, Aldous Huxley, Evelyn Waugh and Robert Graves also turned down honours.

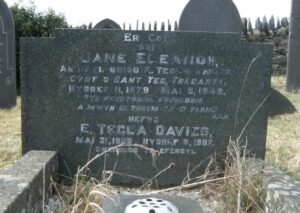

Edward Tegla Davies died in 1967 and was buried alongside his wife Eleanor (he used to call her ‘Nell’) in Gelli cemetery, Tregarth.

In the centre of the gravestone is a poetic couplet: Yn feunyddiol fonheddig. A mwyn ei threm yn ei thrig. I am grateful to Elin Alaw for providing me with the following explanation and translation.

The epitaph on the gravestone is an example of a couplet in the cywydd deuair hirion meter. It has been composed in full cynghanedd, meaning that the consonants from the first half of each line are repeated in the same order in the second half. This is a pattern that occurs in both the Welsh bardic tradition (which we call Cerdd Dafod, lit. music of the tongue) and in the Welsh musical tradition (which we call Cerdd Dant, lit. music of the harpstrings). As for the meaning, it’s a description of Nell as courteous every day, and of a tender appearance (mwyn ei threm) in her abode (trig). If the poet had been referring to a man, he would have said ei drem rather than ei threm, so it’s a description of Nell rather than Tegla. I wonder who wrote the couplet? I don’t associate him with poetry, but it wouldn’t surprise me at all if it’s his own work. Then again, a quick read of Wikipedia shows that he was a close friend of T. Gwynn Jones, one of our greatest strict-metre poets. It would be interesting to find out.

I have very much enjoyed researching my great grandfather. I love how he never took his dog collar off, even on the beach – not from pomposity but from a desire to be easily spotted by anyone who might need the help of a minister. I love how he entertained his grandchildren by drawing faces on acorns, and moved his congregation to tears of compassion for his raucous attempts at ‘tuner’ preaching. I love that he was almost as concerned for the sheep struck by lightning as for the schoolboys saved from it.

I can’t help wondering how Tegla would have applied his talents to today’s fiction market. In his day, literary critics viewed fiction-writing and preaching as a dodgy combination. Even more so today. Every how-to book on my writing shelf condemns ‘preachiness’ and ‘moralizing’ as the two unforgivable sins of the modern author. But I can’t help admiring the passion and integrity of this Welshman who let Christ shine brightly from every word he wrote. He never took his collar off – neither on the beach nor in his books.