Author: Stephen

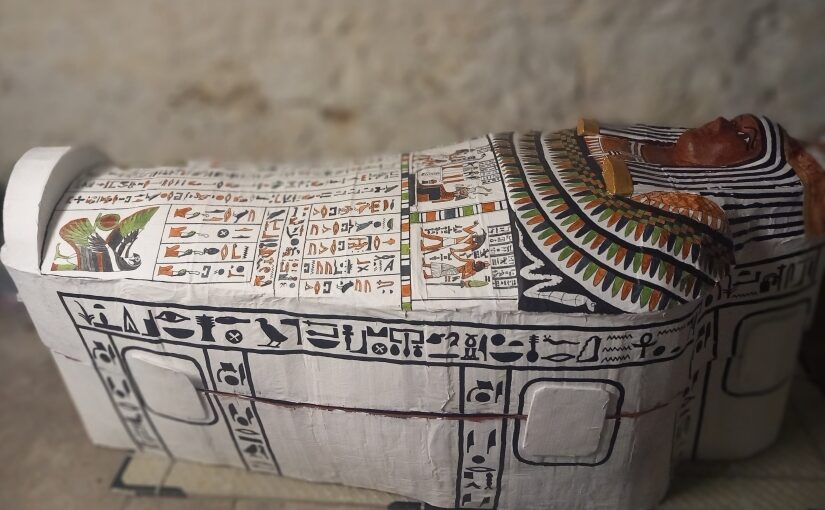

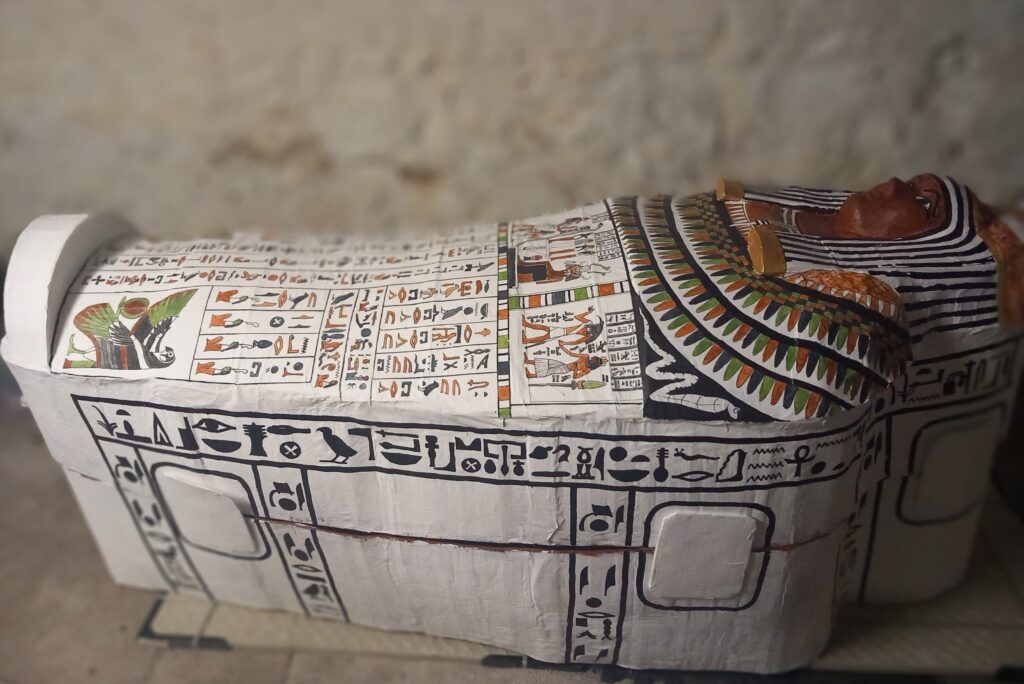

How to make a papier-mâché Ancient Egyptian coffin

For a fun project over the summer, I had a go at making an ancient Egyptian coffin out of cardboard and papier-mâché. I know papier-mâché isn’t the most relaxing of classroom activities but when I do it at home with an audiobook playing in the background, I find it extremely therapeutic. Maybe a project of this size is feasible in Year 3 or Year 4 if a group of fifteen or so children team up and spread the work across several afternoons.

I based the design on the coffin of Pensenhor in the British Museum and used instructions from Andy Seed’s excellent blog post I Want My Mummy.

You can get free fridge-freezer-sized cardboard boxes from any white goods company – the ones I approached were glad to be shot of them. I used a roll of packing tape to assemble the cardboard ‘carcass’ of the coffin, and cut out eight curved panels on top to provide the shape of the body. As for the face, you can buy a paper mask from Hobbycraft or similar.

I messed up here – the cardboard hair-piece should curve up over the brow instead of sitting flat. Otherwise I was pleased with the coffin’s shape.

Two layers of papier-mâché followed by two coats of white emulsion. Once it was dry, I slit it horizontally with a craft knife to divide the coffin into top and bottom sections. Because the two halves were originally one piece, they fit together perfectly.

Use Posca pens or similar to draw rectangular panels for the artwork and hieroglyphs.

I used acrylic paints (Shuttle Art vintage paints) for the picture panels and hieroglyphs. A limited palette is probably best. I stuck to dark blue, sage green and ‘Mars’ orange, to imitate the real coffin of Pensenhor.

Finally, I added two coats of Polyvine ‘clear satin’ varnish, for protection. I wish I had chosen a flat varnish – the face in particular has ended up too shiny.

I’m using the finished coffin as a prop for an escape room and as a visual aid for online Egypt-themed author visits. Book me for an author visit through Authors Abroad to meet Pensenhor for yourself and to enjoy a special Night in the Museum writing workshop.

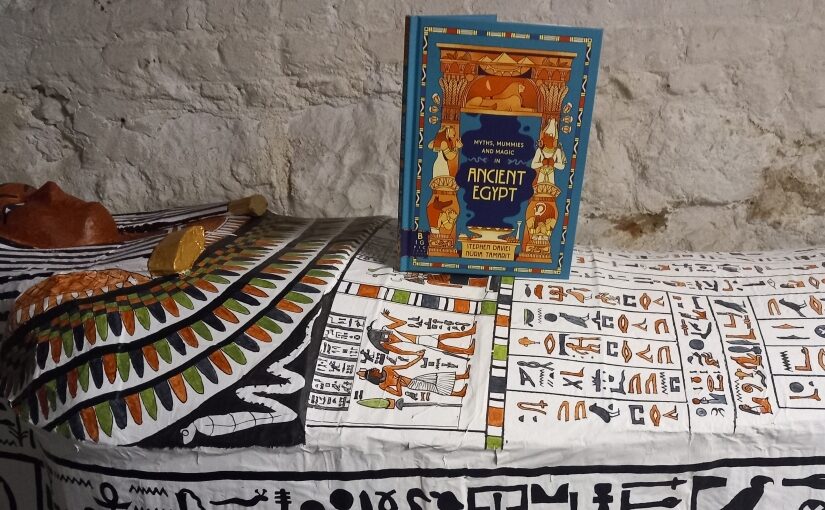

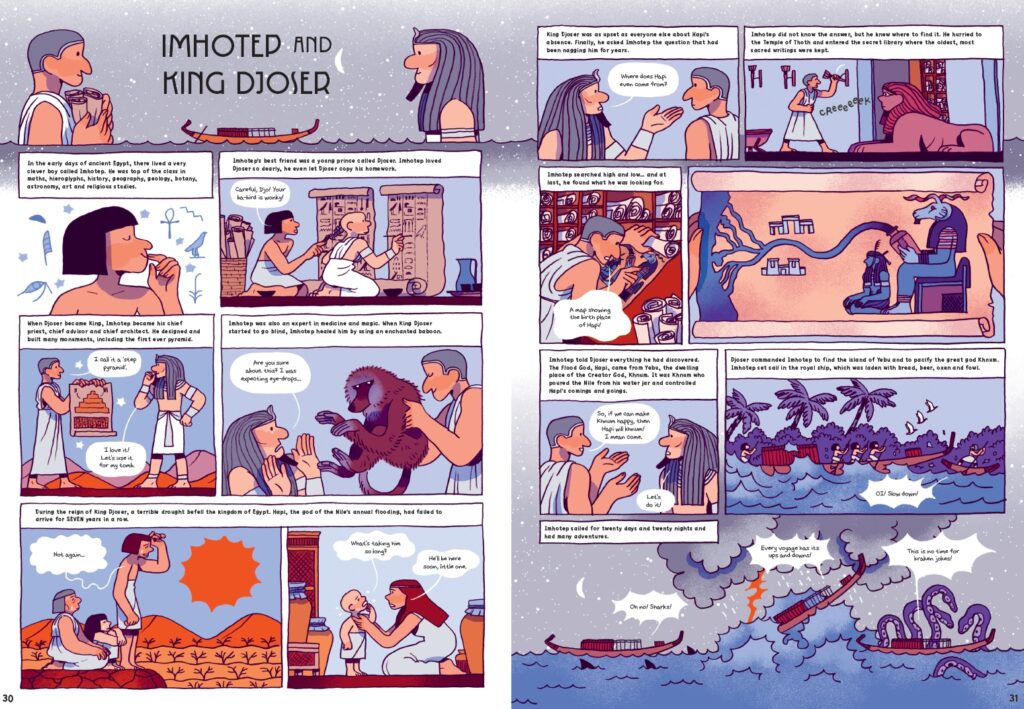

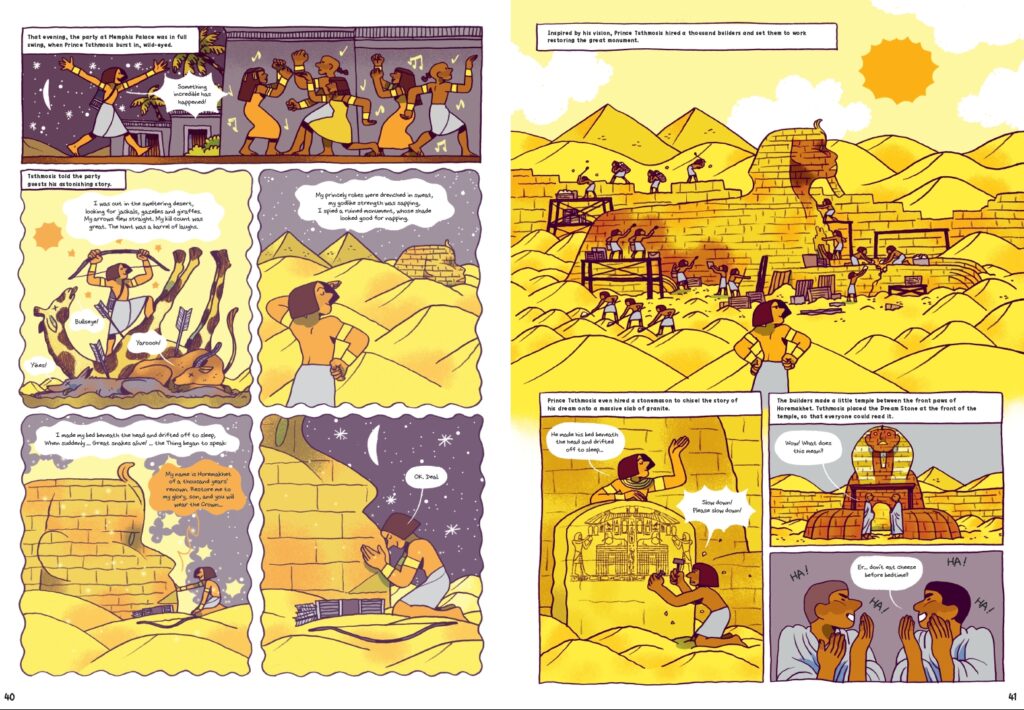

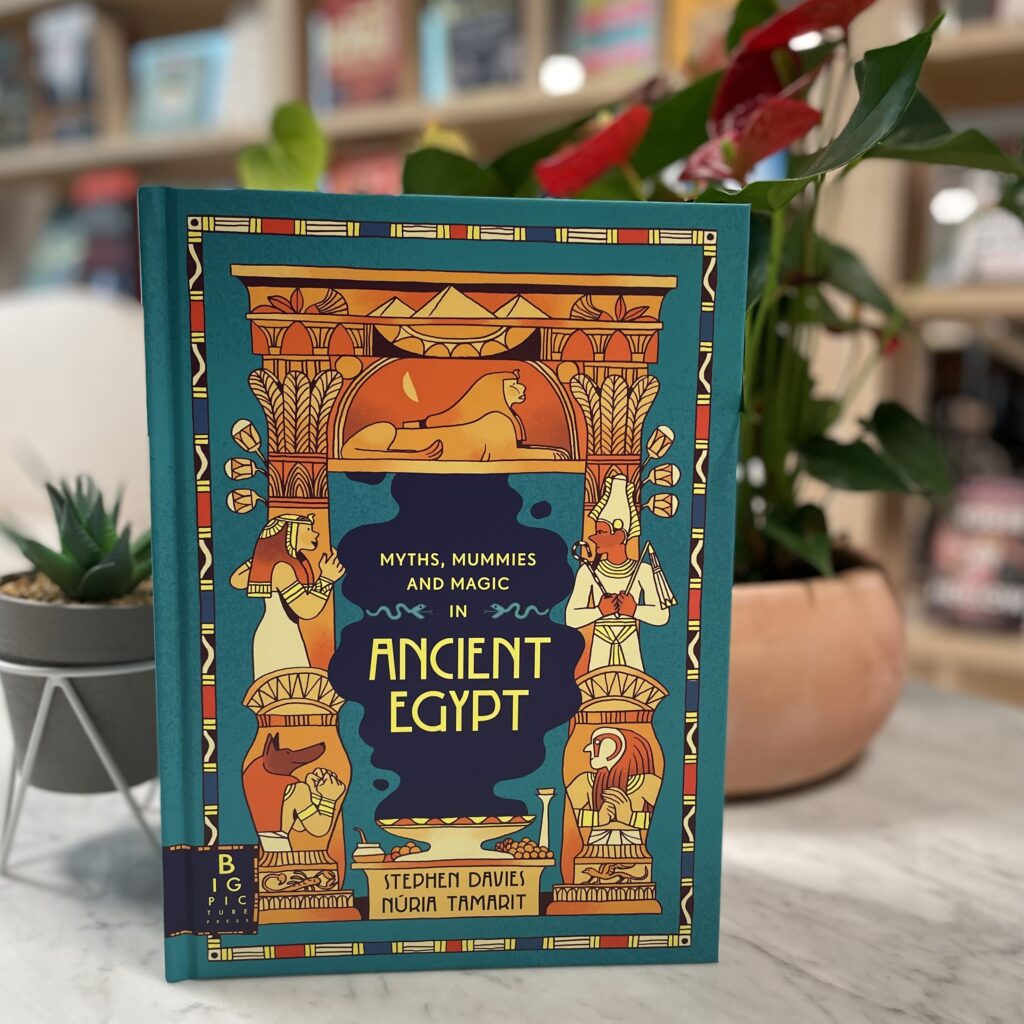

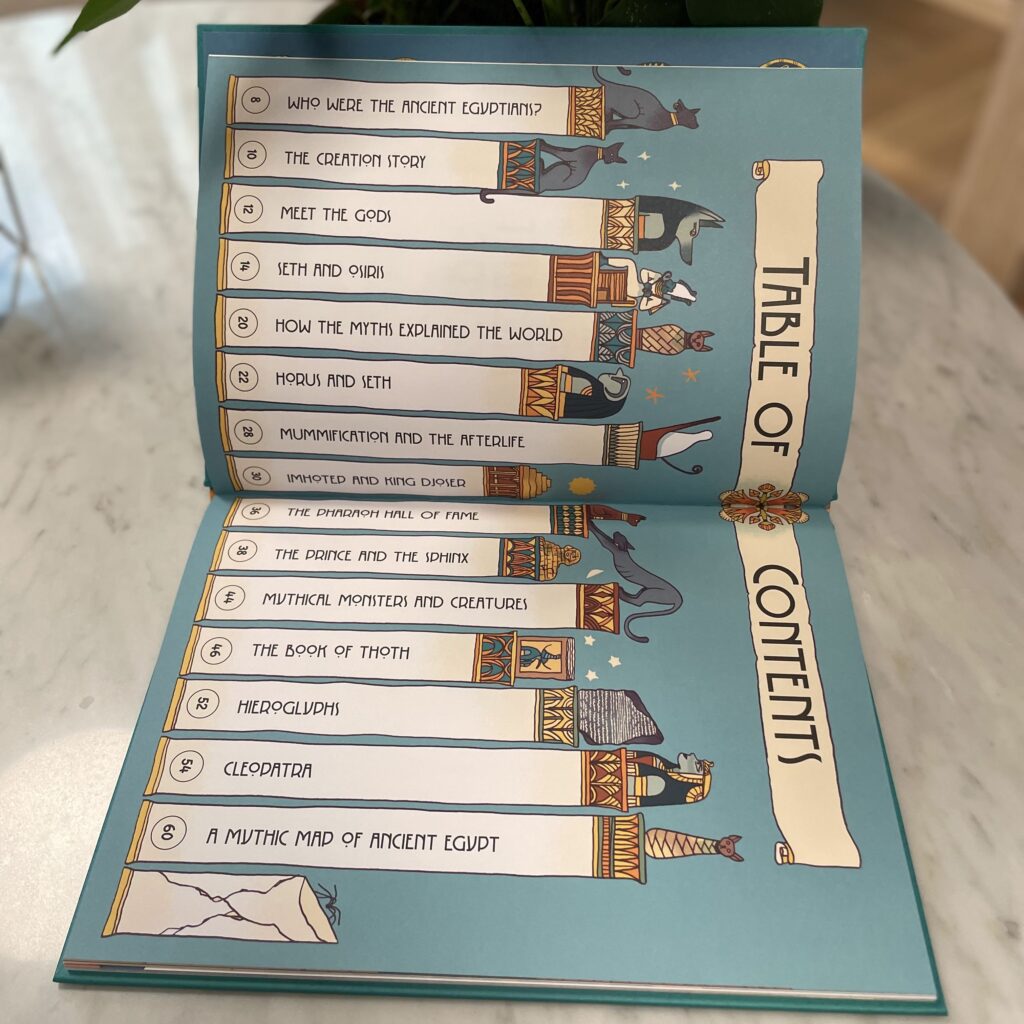

Myths, Mummies and Magic in Ancient Egypt

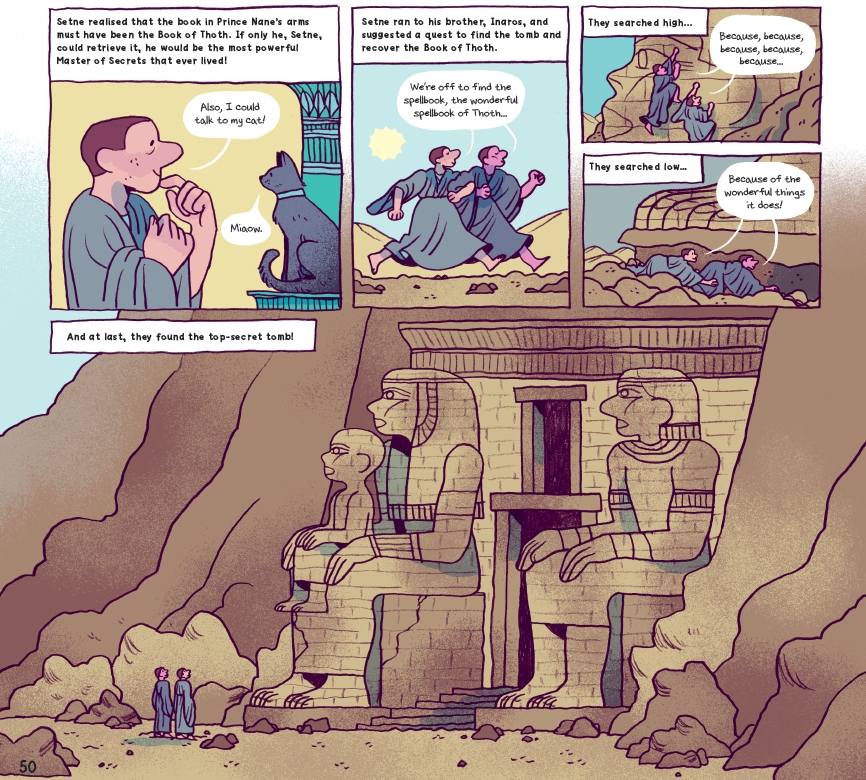

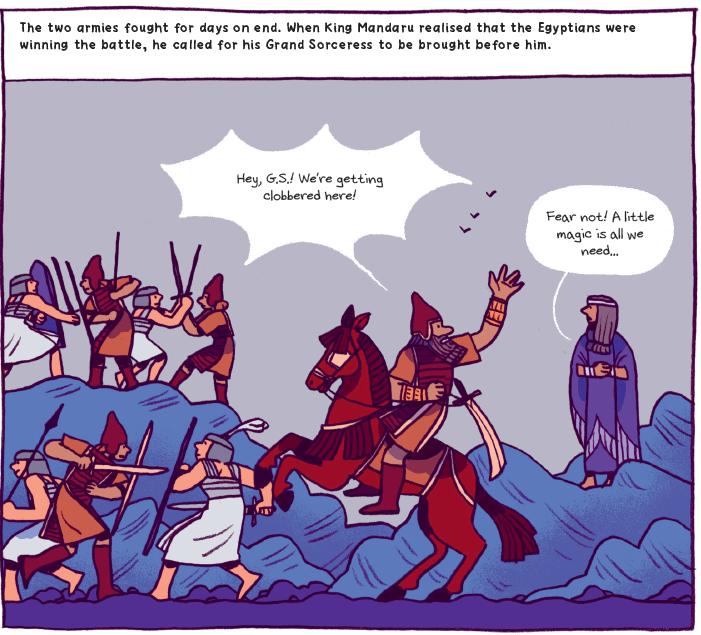

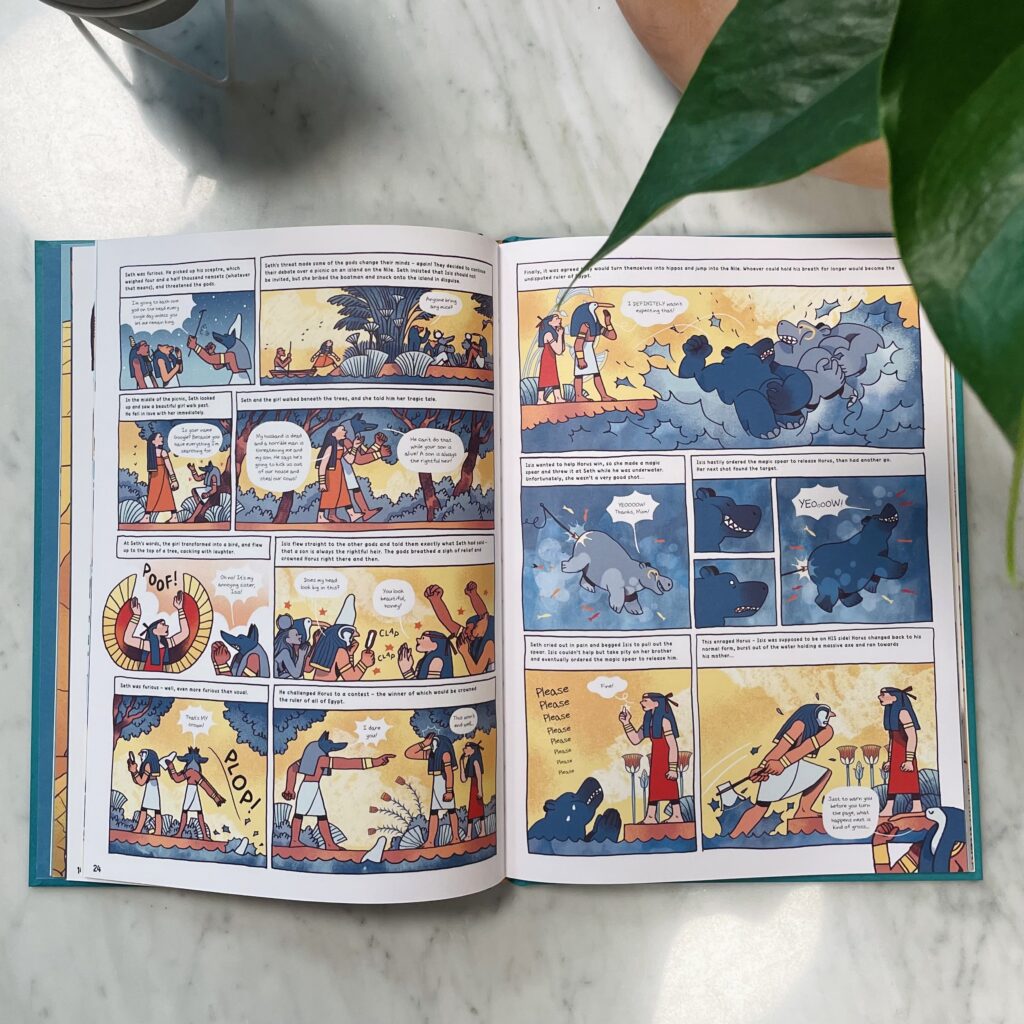

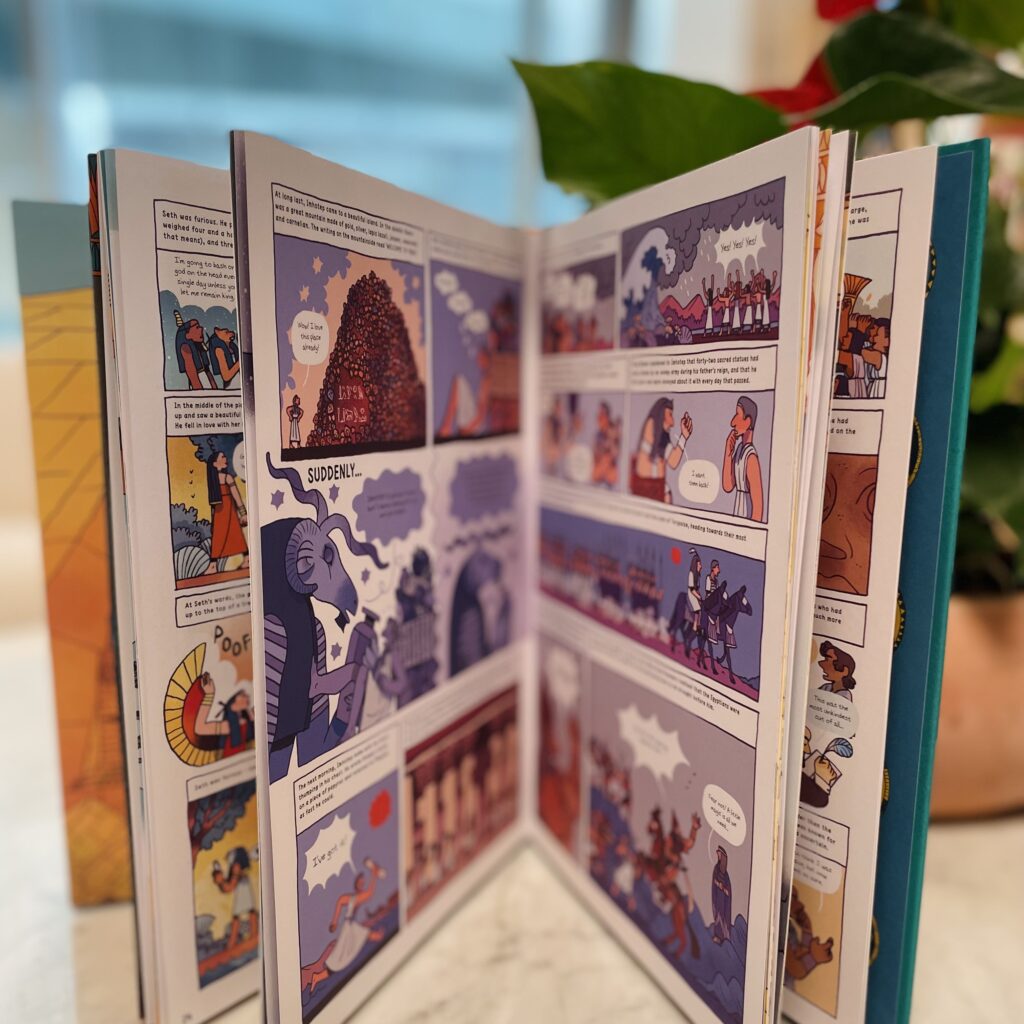

My new book is out now, and it’s an absolute beauty, thanks to stunning illustrations by Núria Tamarit. It contains six comic style tales, bursting with mythical creatures, gods, pharaohs and adventure.

I was thrilled to receive an early review from the queen of historical fiction herself.

This new hardback about Egyptian mythology and history is superb. Witty and informative, it is also child-friendly. And the full colour illustrations are wonderful. Perfect for any kid 7+ who loves ancient history.

Caroline Lawrence, author of The Roman Mysteries

The stories in the book were sourced from all over Egypt. This one about Imhotep is from Sehel island in the middle of the Nile – thirty-two columns of hieroglyphs etched onto a boulder.

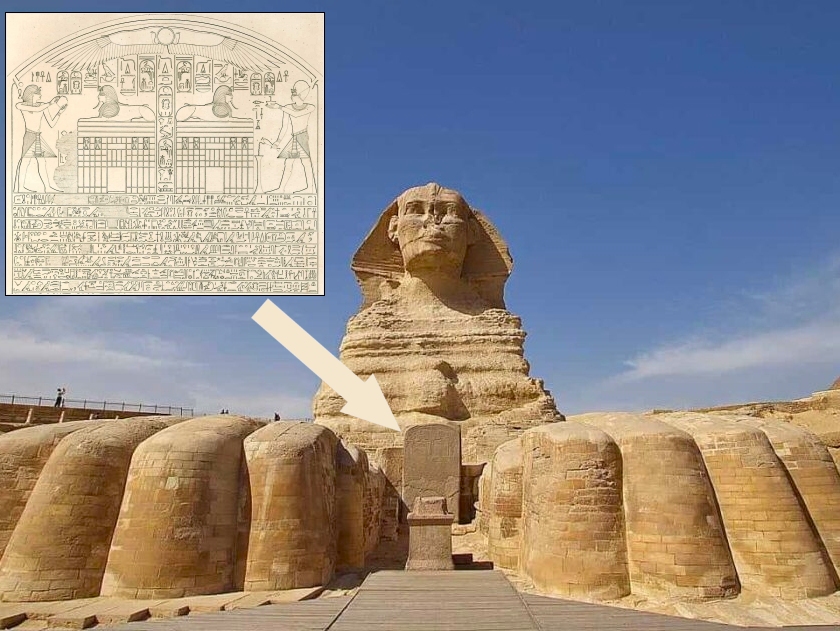

This next one (a wild account of a pharaoh’s dream) is from a block of granite which was discovered between the paws of the sphinx at Giza.

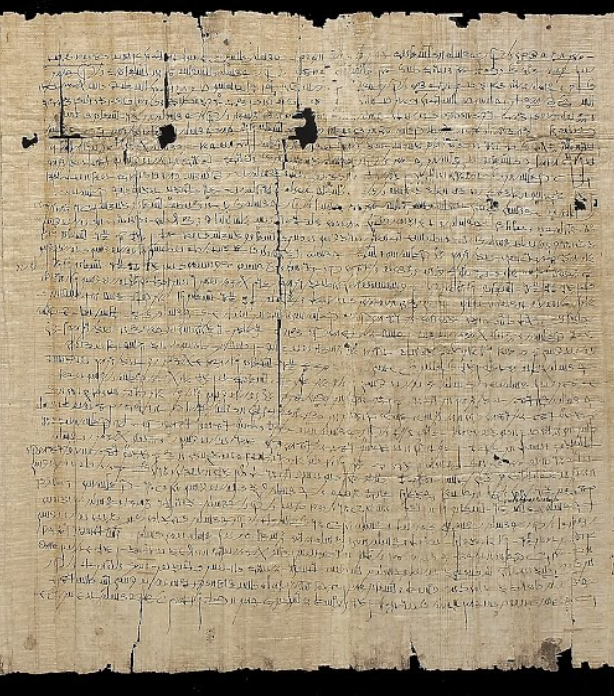

This one (a magician on a tombraiding quest for the Book of Thoth) is Papyrus 30646 in the Egyptian museum in Cairo.

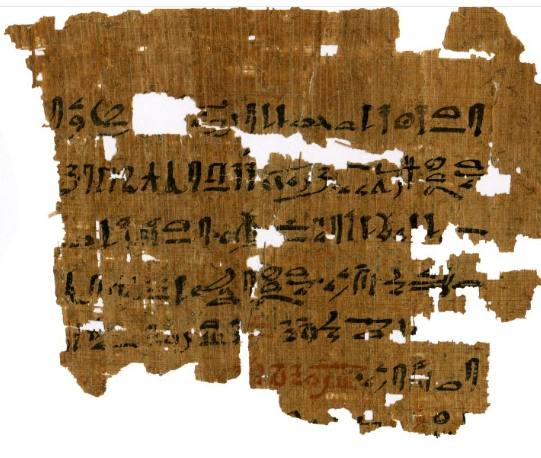

Our retelling of Imhotep’s epic face-off against an Assyrian sorceress is from fragments of papyrus discovered in Tebtunis, Lower Egypt. Thanks to Professor Kim Ryholt for allowing us access to this mindboggling story, which has only recently been pieced together and translated.

When I was a teenager, I spent a lot of time writing and drawing comic strips. Last year, as I worked on these Egyptian tales with Núria, I kept getting a dizzying tingle of déjà vu. What a treat to revisit a childhood passion.

You can buy MYTHS, MUMMIES AND MAGIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT from any of the usual outlets. Here is a link to a few of them: buy the book

Buy a book with Nano (XNO)

The cryptocurrency Nano (XNO) is fast, feeless and environmentally friendly, so I am glad to accept Nano as payment for the epub version of my bestselling book The Ancient Egypt Sleepover. I look forward to the day when Nano is accepted everywhere. In the meantime, this is my tiny contribution to that goal.

Click here to buy The Ancient Egypt Sleepover (epub) with Nano.

Or click the cover below to learn more about the book.

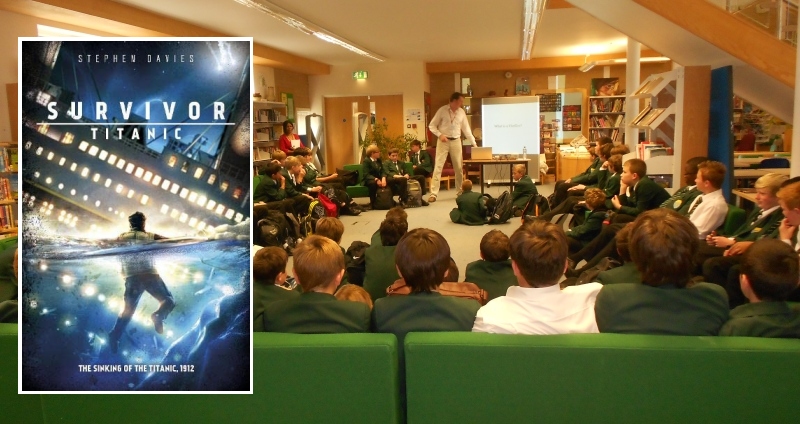

Titanic Writing Day for Key Stage 2

If you are a Year 5 or 6 teacher and your class is studying the sinking of the Titanic, please note that I now offer a Titanic-themed author visit. We can do this right at the start of your Titanic unit (as a hook to create interest) or later on when the children have already been studying the topic for some time. It may be that your pupils are already reading my book Survivor Titanic but this is not essential.

Content

The day starts with an hour-long assembly for the whole year group. We do a Titanic-themed quiz (harder or easier questions, depending on how much the children have already studied the topic) and then discuss the importance of primary sources: photographs, deck plans and survivor accounts.

We look at Jack Thayer’s exciting first-hand survival narrative, which influenced Jimmy’s escape story in my own book, and beginning imagining our own passenger on the Titanic, a potential protagonist in an adventure story of our own making.

After the assembly, I lead a writing workshop with each class. The timings for these workshops are entirely flexible, depending on how many classes you want me to work with – anything from one to three classes works well.

Over the course of the workshop, I guide pupils in planning their own survival stories set aboard the Titanic. We work on characterization, suspense and Show Don’t Tell. The workshop is punctuated by short bursts of speed-writing by the children. By the end of the day, pupils should be well on the way to completing the first draft of a short story, a task which could perhaps be completed or redrafted for homework.

The day ends with Q & A and then children have the opportunity to share some of their writing. I give plenty of affirmation and encouragement, along with gentle suggestions for improvement. When I do Titanic themed KS2 visits, pupils often end up wanting their own copy of Survivor Titanic. I am happy to bring copies with me for sale and signing.

Testimonials

Steve’s visit was brilliant; it was a really engaging day that left our Year 6 pupils excited to write. It was great for them to see the process a real author follows when planning a new story and showed them the importance of knowing their characters! Steve created a great atmosphere for learning, celebrating everyone’s ideas and pushing them to think more deeply. The stories produced as a result were excellent and really showed that they’d taken his advice on board.

Ms Jelley, Year 6 teacher, King’s Park Academy, Bournemouth

Stephen Davies has visited our school twice now, and on both occasions the children have been truly inspired. The topic of the Titanic intrigues the children and Stephen’s presentation, knowledge and explanation of how he researched the historical event to write his novel captivated them. The writing workshop engaged all pupils and enabled them to create their own character and consider ways to bring them to life, which resulted in the children producing some outstanding pieces of writing. They thoroughly enjoyed the day because of Stephen’s inspiring words and the time he spent talking to them about books, authors, their interests and his experiences. Fantastic, amazing and inspiring are some of the words used by our children to describe the day, with many commenting that they are now considering becoming an author in the future.

Ms Rochelle, Year 6 teacher, Park Hall Junior School, Walsall

We couldn’t recommend Stephen enough. His knowledge of Titanic was extraordinary and the children were engrossed with the stories and knowledge he could share. The aim of the session was to learn more about the Titanic but also to support our children with story writing. Stephen’s workshop was invaluable. The children were very excited to write their stories and use the advice given from Stephen – their stories were out of this world!

Ms Foster, Year 6 teacher, Manor Community Primary School, Swanscombe

This letter is a thank you for the amazing assembly and class workshop. I found both sessions really inspiring. I appreciated your picking me to get up and share facts about the Titanic. I felt really proud. Another thing that I enjoyed was the class quiz. It was a shame that our class lost. I enjoyed designing my own character that I could later on use in my own survival story. One of the best parts was transferring my planning into an amazing story.

Kerim, Year 6, King’s Park Academy, Bournemouth

Steve visited our group of Y6 pupils as part of our history topic where we were exploring different sources of evidence linked to the Titanic. During his visit, he exposed the children to a range of primary sources such as deck plans, photos and survivor accounts, introducing the children to life on board the ship. As a result of viewing these sources, the children were able to imagine their own character and setting for a short piece of narrative in the first person. Steve also told the children about a young man on board called Jack Thayer who was the inspiration for his own character ‘Jimmy’. The children were incredibly engaged by Steve’s presentation, enjoying the opportunity to ask further questions about the Titanic and listening to him read a few chapters from his book.

Years 6 teachers, Mosborough Primary School

It was a fantastic day which brought our topic to life and sparked the imagination of our children. We would definitely recommend anyone embarking on this topic to invite Steve in!

To book a Titanic-themed author visit, please write to Yvonne Lang at Authors Abroad: yvonne@caboodlebooks.co.uk or contact me for further details.

8 children’s books about the Titanic

Many children are fascinated by the story of the Titanic and it is often studied in primary schools, particularly in Key Stage 2. There are many excellent children’s books on the subject.

Before I continue, I should declare an interest. KS2 teachers often choose my own book Survivor Titanic to accompany their Titanic unit, especially in Year 5 and Year 6.

Mandy Southgate at Addicted to Media reviewed the book:

It is rare that an author manages to cram so much information and knowledge into a story without weighing it down but Survivor Titanic proceeds at a breakneck pace. If the aim of the Scholastic series is to teach the history curriculum in an exciting and thrilling manner, then they have certainly succeeded with this first release.

Last plug: I also offer a full day or half day Titanic writing day, guiding children step by step through the process of writing their own exciting historical fiction set on the sinking ship. See here for details.

Here are eight of the best children’s books about the Titanic – four non-fiction and four fiction – in no particular order.

Non-fiction

1. Story of the Titanic

When it comes to portraying the details of this disaster, show don’t tell is key, and cutaways are definitely the best way of showing the inside of the Titanic both before and after the iceberg struck. Steve Noon’s book is highly recommended by Titanic geeks on Encyclopedia Titanica, as well as on Amazon. A real feast for the eyes.

2. Titanic (Eyewitness)

More Show-Don’t-Tell from another sumptuous DK picture book. Really brings the story alive with anecdotes, secrets, facts and puzzles. Perfect for homework projects about the Titanic tragedy.

3. On Board the Titanic: What it was like when the great liner sank

Tanaka’s book uses real historical characters to tell the story. Jack Thayer’s account is particularly interesting. He was seventeen at the time of the sinking and was one of the few men to stay on the Titanic until the very last minute and still survive. A thrilling true-life story.

4. Inside the Titanic

Ken Marschall made a name for himself for lavish illustrations of books about the Titanic, and this is probably his best one. Like Steve Noon, he uses cutaway illustrations to make readers feel they are actually inside the doomed liner. The real-life accounts of passengers focus on the children aboard the Titanic, which is a particularly compelling (and harrowing) approach.

Ken’s paintings almost seemed to be stills from a movie that hadn’t yet been made. And I thought to myself, I can make these paintings live. It became my goal to accomplish on film what Ken had done on canvas, to will the Titanic back to life.

James Cameron

Fiction

There are dozens of children’s books set on the Titanic, including several time travel offerings where a modern-day hero gets transported back to 1912. The four I have chosen are not time travel stories, but they have all proved popular with young readers.

I SURVIVED is historical fiction, describing ten year-old George Calder’s battle for survival. Lauren’s book is gentle fare, especially considering the terrible setting, but it is well researched and enduringly popular.

Michael Morpurgo’s KASPAR PRINCE OF CATS is an absolute classic. Insired by Michael’s time as Writer in Residence at the Savoy Hotel, this book is charming, evocative and unpredictable, and it deals with mature themes in a very elegant way.

I can’t survey children’s books set on the Titanic without mentioning POLAR THE TITANIC BEAR. Another classic with beautiful full-page colour illustrations. Polar is a teddy bear, of course, and this is the Titanic as told through his eyes. Starts with him being sewed and stuffed in the factory and ends with- well, that would be telling.

TITANIC: MY STORY by Ellen White is the thrilling story of a young orphan Margaret Anne who can hardly believe her luck when she is chosen to accompany wealthy Mrs Carstairs aboard the great Titanic. This is a really good read, but something of a slow burner. It takes a while for Margaret Anne to get aboard the Titanic. When she does, the story is unputdownable.

The Nightjar’s Complaint

Why did you make me a nightjar, Ma,

Such a portly unmuscular bird?

Why must I flitter this tortuous path

And emit this crepuscular churr?

Do you hear the night birds ridicule

Our spooky flap and vulgar cry?

“You Goatsuckers!” the horned owl twoos,

“You cooky Caprimulgidae!”

“You sprogs of Nyx,” the barn owl twits,

“Dark harbingers of puckeridge.”

I’m tired of being a nightjar, Ma,

Reviled by everything that flies.

“Yer beak been to the sawmill, lad?

Some Martian lend you ‘is eyes?”

Why do we have to be nightjars, Ma,

With wings like bark and legs absurd?

Hark now the mother wren invokes

Us dreaded bogeybirds:

“Don’t run afoul, my darlings,

of the gothic horror Moth Owl,

of the Corpse Fowl with the cog growl,

of the gurning, turning Fern Owl.

Be good, my little hatchlings, or

the Fly-toad will get you,

the Poor-will will deck you,

the Dor-hawk will peck at your heads.

The Nightmare Bird, believe you me,

will leave you all for dead.”

Pass the homebrew bottle, Ma,

It’s not just fowl wot’s cruel.

I’m chieftain, Aristotle says,

Of mischief and misrule.

The nightmare catfish-cuckoo flies

From demon mother Lilith’s womb,

He harvests children unbaptized

and supervises Edom’s doom.

We pass the farm, the ewegoats flee.

‘Bums to the fence, girls,’ Nanny bleats.

‘Those suckers fell out of the ugly tree,

Keep your udders away from their beaks!’

A fleeting shimmer of red silk fur –

Et tu, vulpus vulpus?

Do you, too, vanish at the churr

Of fiendish Caprimulgus?

The birds and the beasts teach us villainy, Ma.

They court their own destruction,

When we return from Cote d’Ivoire.

We’ll better the instruction.

We’ll rage with raucous toad-like tune

And wage blunt-headed battles,

Then fling our heartache to the moon

with our last

robotic

rattles.

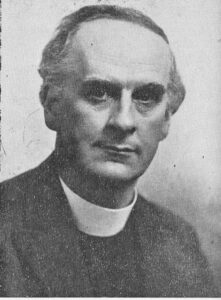

Edward Tegla Davies

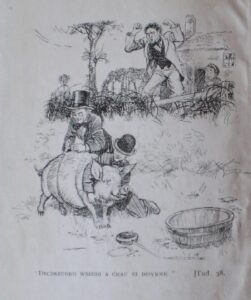

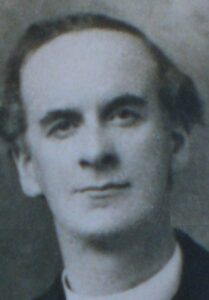

When my first book was published back in 2006, Dad told me about my great grandfather Edward Tegla Davies, who was a Methodist minister and children’s author. Dad showed me an old copy of Nedw, one of Tegla’s best known works. Nedw in Welsh is short for Edward and is pronounced Ned-oo. The language is natural (according to Lionel Madden, author of Methodism in Wales, Tegla ‘wrote as children spoke’) and the style is gentle and wry – very different from the rather severe religious stories commonly offered to children at the time.

Nedw was illustrated by Leslie Illingworth, who was political cartoonist for the Daily Mail and contributed to Punch and other magazines.

Tegla made quite a splash on the Welsh literary scene, writing for adults as well as children. He has a brief wikipedia page in English (Edward Tegla Davies) and a fuller one in Welsh (Edward Tegla Davies). There is also a long entry on the website Welsh Biography Online, which includes this gem:

Tegla regarded himself as a rebel all his life. Although he was one of the most prominent preachers and one of the most influential men of his denomination, he did not refrain from criticising and satirising organizational systems, whether religious or secular.

Dad recalls that his grandfather was kind and gentle, that he always wore his clergyman’s collar (even on the beach!) and that he had various stock party tricks to amuse the grandchildren. On country walks he used to collect acorns, turn them upside-down and draw faces on them, so that the acorn’s cup resembled a hat. Tegla possessed the rare gift of having stayed in touch with his inner ten year-old, a gift that equipped him well for his children’s writing.

Edward Davies (pronounced Davis) assumed the name Tegla when he was ordained as a Methodist minister – there was already an Edward Davies in the ranks and he needed a distinct appellation. He took the name Tegla from the name of his birthplace Llantegla (lit. Church of Thecla) in north Wales. Saint Thecla was a first-century saint about whom various apocryphal stories are told. The name stayed in the family for two generations – my grandfather and father were both given it as their middle name, but I was not.

At the age of 14, Edward Davies was a pupil-teacher at Bwlch-gwyn school in north Wales. Promising pupils who completed primary school would sometimes be asked to stay on as teachers – classroom assistants, most likely – and this is what Edward did. He was greatly influenced by a young teacher there called Tom Arfor (pronounced Ar-vor) Davies, who ‘awoke his interest in the history and literature of Wales’ (citation). Dad tells me that the Edward was present when his teacher started coughing up blood, and that he died shortly afterwards. It was in memory of Tom Arfor that Edward later named his own son (my grandfather) Arfor. But the legacy of Tom Arfor was more than a name. A passion for reading and writing had been stoked in the young teenager.

From his reading of the Welsh classics, Edward acquired ‘a Welsh prose style of great purity and naturalness’ and ‘although he never had a Welsh lesson at school nor went to university, he became one of the most prolific writers in Welsh.’ (quotation from Rev. Dr Islwyn Ffowc Elis, Welsh Biography Online).

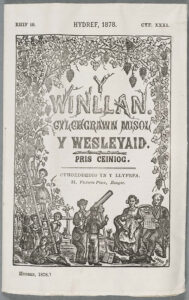

Edward (often called by his middle name ‘Tegla’) contributed boys stories to a Welsh language magazine called Y Winllan (The Vineyard), of which he became the editor. The stories were eventually published as books in their own right. The first to be released was Hunangofiant Tomi (Tomi’s Life, 1912), the fictional diary of a country boy in north Wales. It was gentle and wry in tone, documenting Tomi’s various adventures and scrapes. There followed Nedw (Ned, 1922), Rhys Llwyd y lleuad (Rhys Llwyd the Moon, 1925), and Y Doctor Bach (The Little Doctor, 1930).

According to the Welsh literary critic Meic Stephens, Tegla’s boy heroes were ‘mischevious, dreamy and tricksy’ (citation). In the story Do Zebras, for example, a boy called Birch and his friend Humphrey paint a donkey to look like a zebra. Tegla’s characters remind me of William and the Outlaws (Ginger, Henry and Douglas) from Richmal Crompton’s much-loved William series. In 1922, the same year as Do Zebras was published in Bangor, the first William book Just William was being published in London. And by strange coincidence, chapter five contains a scene in which William paints Henry’s dog blue as a circus exhibit.

“Blue dog,” said the showman, walking forward proudly and stumbling violently over the cords of the dressing gown. “Blue dog,” he repeated, recovering his balance and removing the tinsel crown from his nose to his brow. “You never saw a blue dog before, did you? No, and you aren’t likely to see one again, neither. It was made blue special for this show. It’s the only blue dog in the world. Folks’ll be comin’ from all over the world to see this blue dog—an’ thrown in in a penny show! If it was in the Zoo you’d have to pay a shilling to see it, I bet. It’s—it’s jus’ luck for you it’s here. I guess the folks at the Zoo wish they’d got it. Tain’t many shows have blue dogs. Brown an’ black an’ white—but not blue. Why, folks pay money jus’ to see shows of ornery dogs—so you’re jus’ lucky to see a blue dog an’ a dead bear from Russia an’ a giant, an’ a wild cat, an’ a China rat for jus’ one penny.”

Just William, chapter 5, Project Gutenburg

Rhys Llwyd the Moon is a collection of stories about a small moon (!) and the adventures it/he has with a couple of boys in rural Wales. The word surreal is often used when writing about Tegla’s books, and you can see why. The book’s popularity was helped by the fact that it contained six black and white illustrations by the popular children’s book illustrator and landscape artist William Mitford Davies.

The Davies & Davies author/illustrator team also produced Hen Ffrindiau (Old Friends, 1927). The old friends alluded to in the title are Welsh folk tales, popular rhymes and proverbs. Here you will find witty anecdotes about the red-faced cobbler of Rhuddlan, the yellow foal, the mountain chicken and other absurdities. This is a real classic – a book for children of all ages, including adults. I dearly wish that there existed an English translation of this one. This was the first of several fantasy novels by Tegla, including a book of Welsh fairy tales Tir y Dyneddon (Dyneddon Land, 1921) and Stori Sam (The Story of Sam, 1938 ).

Tegla also wrote a novel for adults. Gwr Pen y Bryn (The Master of Pen y Bryn, 1923) was serialized in the periodical Yr Eurgrawn (translation, anyone?) before appearing in book form. It is Tegla’s only novel that was translated into English. It has as its background the Tithe War of the 1880’s and describes the Christian conversion of a rich farmer called John Williams. Emeritus Professor Robert Maynard Jones (1929-) called it ‘one of the most impressive novels of his time’ (citation). Lionel Madden related how the book was described “with pardonable exaggeration” as “the greatest Welsh novel”.

But the novel also had its detractors. It was decried by one leading critic on the grounds that Tegla had insisted on ‘saving’ his central character. ‘Whatever its shortcomings,’ wrote novelist Islwyn Ffowc Elis, ‘The Master of Pen y Bryn is a milestone in the history of the Welsh novel because of its ordered plot and its penetrating study of a soul in anguish.’

Y Winllan (The Vineyard) was a Wesleyan magazine for children, published monthly in Welsh. Edward Tegla Davies started off as a reader of Y Winllan, then became a contributor and finally became its editor.

In 1878 the copy you see here was placed inside a glass bottle and hidden behind one of the foundation stones of a new Welsh Wesleyan Chapel in Aberystwyth. The chapel closed in 1992 and the bottle was discovered in 1999 whilst work was being undertaken to convert the building into a tavern.

Edward Tegla Davies was in his mid-twenties during the Welsh Revival, a period of explosive church growth in Wales in 1904-5 that sparked a Christian ‘awakening’ in many other countries. During that time, taverns were going bankrupt and churches were full to bursting. According to the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, Tegla had a conversion experience after attending a preaching festival at Coedpoeth, and decided to enter the ministry. In the course of his life he ministered in Abergele, Leeds, Menai Bridge, Port Dinorwic, Tregarth (thrice), Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant, Denbigh, Manchester (twice), Liverpool, Bangor and Coedpoeth.

Lionel Madden writes:

Tegla was not a natural preacher, but he laboured to make himself effective. Here he describes his early efforts.

I was born into the tradition that you were not a preacher unless you were a ‘tuner’ (one who employs sing-song cadence in the delivery of a sermon). I would do my best, making myself terribly hoarse and leaving me with a very sore throat on a Monday morning. I was envious of those tuners who could provoke tears, for the proof of a successful service in those days was that the congregation was in floods of tears. The only tears I could conjure up were tears of compassion for my raucous attempts.

He moderated his preaching style, adopting a more conversational approach, but never quite lost the sense of strain. There were, however, other features that more than compensated for this and propelled him into acceptance throughout Wales as one of the leading preachers of his day. He was a master of apposite illustration and of clear exposition. His idealism ran alongside a fiercely critical mind, and the boldness with which he advanced one or the other made what he said perpetually challenging. Above all he appeared to be a prophet for his time.

Tegla did not prize preaching for its own sake, and his tone was wry when he wrote about the ‘tuners’ and the ‘two-sermon-a-night’ preaching meetings. He was more interested in ongoing discipleship, and for this the home setting was more significant than the church.

I am firmly of the opinion that the smallest contribution to the spiritual life of the Church in my time has been preaching at preaching meetings. I am convinced that the chief reason for our intellectual and spiritual poverty, and our lack of influence in the world, is that we have failed to educate our children, young people and all ages, in the basic principles of our faith.

It is no surprise, then, that many of Tegla’s stories for young people touch on spirituality. One of the tales in the collection Hen Ffrindiau (Old Friends, 1927) was called Samuel Jones the Hendre. Here are the bare bones of the story:

There were two farmers at harvest time: Samuel Jones the Hendre and Mr Herbert Fron. Samuel Jones’ land was very poor compared to Mr Herbert Fron’s fertile and copious land. When it was decided to decorate the chapel for the Thanksgiving Service, most of the fruit and vegetables came from Mr Herbert Fron’s fields and green houses. Samuel Jones was not at all happy about this, as he could only offer thorns and brambles. Shortly before the service began, Samuel Jones crept into the church and slyly exchanged Mr Herbert Fron’s abundant crops for his own thorns and brambles. The outcome was that everyone refused to participate in the service. They said that it was impossible to thank God in the middle of thorns and brambles. Everyone refused, except for one, and that was Samuel Jones himself. He had remembered a verse from Isaiah 66 – “Has not my hand made all these things?” – and he worshipped happily alone, surrounded by his thorns and brambles.

Another of Tegla’s works for children tells the story of the Holy Grail. In the post Davinci Code era we tend to think of Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland as the final resting place of the Grail, but medieval specialist Dr Juliette Wood believes that Wales has a much stronger thread of grail legends. In March 2013, Dr Wood delivered a lecture at the Museum of London entitled The Phantom Cup that Comes and Goes, giving evidence for the Welsh claim and making reference to Tegla’s work:

Edward Tegla Davies (1880-1967), a well-known Wesleyan Methodist minister, produced a charming curiosity called Y Greal Sanctaidd. This booklet for young readers traced the history of the grail legend with the emphasis on its relevance for Wales. Tegla summarized the medieval grail texts, pointed out parallels with early ‘pagan’ Welsh literature, such as Ceridwen’s cauldron, and presented a short exposition on how modern writers, among them Alfred Lord Tennyson, used the motif in their work. The focus was on the spiritual meaning of the grail and its continued relevance to Welsh life, but the distinctiveness of Tegla’s book lies in the fact that it is aimed at a young audience.

None of my great-grandfather’s works for children are available free online in translation. All I could find in English is the adult essay That Grave from his book Gyda’r Hwyr (At Dusk, 1957). The essay is his account of a country walk with a friend to visit Cardinal Newman’s grave. I was thrilled to find this because it gives real insight into Tegla’s spirituality, his love of nature and his keen critical sense. The whole essay is worth a read, but here are three extracts which I found particularly interesting.

First, Tegla’s thoughts on the fine line between faith and superstition. The passage demonstrates his love of animals and his flair for asking interesting questions.

After going some two or three hundred yards on this get‑away‑from‑it‑all pathway we turned to the left. On one side of the turn is an old shed and on the turn, on a small rise, there is a cross and inscribed on it are the following words:

LAUS DEO. In thankful remembrance of June 30th, 1866, when Divine Providence saved our schoolboys all collected round their father prefect under the adjacent shed, from a sudden thunderstorm when the lightning playing around them struck with death as many as ten sheep about the field and trees close by.

It would perhaps be uncharitable to suggest that as Providence had saved the boys and the prefect it should also have thrown its covering over the poor sheep as well, especially as the ruler of Providence is the author of the parable of the Lost Sheep. By praising Providence in this way does not this testimony also diminish it by making it seem rather miserly in its defensive operations? The line between superstition and faith is a fine one and is quite characteristic of the faith that put up this stone.

And this on the Catholic Church:

There is something hellish in the Catholic Church and there is something heavenly too. It was she who created Catherine de Medici and her followers, whose likes not even Gehenna could have imagined. And it was also she who created Francis of Assisi and his ‘friars’, and not even Paradise could have devised more lovely lives than theirs.

And this, when finally he and his friend arrive at Cardinal Newman’s grave:

We just stand there, not uttering a word, and we stare for a long time, spellbound, and the eloquent simplicity is the most spellbinding thing of all.

And now to another grave, that of Tegla himself.

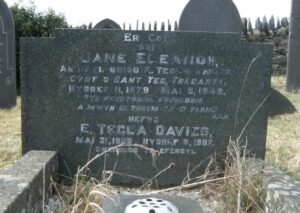

Edward Tegla Davies died in 1967 and was buried alongside his wife Eleanor (he used to call her ‘Nell’) in Gelli cemetery, Tregarth.

He had once said that his writing was just one element in his work as a minister of the gospel, and that he wanted a statement to that effect inscribed on his gravestone. But in the end, he got a different quotation: Yn feunyddiol fonheddig. A mwyn ei threm yn ei thrig. I’m eagerly awaiting a translation of the second bit, but the first bit means ‘Noble daily’.

Noble daily. This is the man who never took his dog collar off, even on the beach – not from pomposity but from a desire to be easily spotted by anyone who might need the help of a minister. This is the man who entertained his grandchildren by drawing faces on acorns, and moved his congregation to tears of compassion for his raucous attempts at ‘tuner’ preaching. A nature lover who was almost as concerned for the sheep struck by lightning as for the schoolboys saved from it. A man who considered himself a rebel all his life, and ended up declining an OBE in 1963, four years before his death.

Why did he decline his OBE? Dad wrote to me that Tegla ‘was never a Welsh nationalist, but he was a patriot, and may not have fancied being honoured by the English monarchy.’ That said, he was not the only writer to decline an MBE, OBE or knighthood. CS Lewis, Roald Dahl, Aldous Huxley, Evelyn Waugh and Robert Graves also turned down honours.

I can’t help wondering how Tegla would have applied his talents to today’s fiction market. In his day, literary critics viewed fiction-writing and preaching as a dodgy combination. Even more so today. Every how-to book on my writing shelf condemns ‘preachiness’ and ‘moralizing’ as the two unforgivable sins of the modern author. But I can’t help admiring the passion and integrity of this Welshman who let Christ shine brightly from every word he wrote. He never took his collar off – neither on the beach nor in his books.

Peony

Soar with me, gentle reader, to the heights

Of Mount Olympus, seat of heavenly bliss,

Where bright-eyed Paeon is apprenticed to

Asclepius the wizened herbalist.

When Heracles’s arrow finds its home

Among the raging veins of Hades’ neck,

Young Paeon plucks th’intruder from its nest

And stems the blood with ginger turmeric.

If artful Diomedes’ singing sword

Should pierce the golden abdomen of Mars

Tis Paeon’s agile hands will heal the rift

with fennel juice and hippocratic calm.

Within the crystal mansion on the mount

Young Paeon salves each wounded titan pride,

Whilst in the shadows old Asclepius

Is not so much green-fingered as green-eyed.

One moonlit night young Paeon stays up late,

To top and tail sweet chamomile roots,

The oak door groans, the artful intern frowns –

There in the doorway stands the bride of Zeus!

Mysterious Leto goddess of the moon

With burnished diadem and silken hair

Cries ‘Hail Paeon, healer of the gods,

Olympian gold in tender loving care!

I’ve watched you gather poppy seeds and dill

and squeeze the flesh of orange bergamot

I’ve seen your ferox resin sleeping pill

and inhalation of forgetmenot,

Yet there is still one secret which evades

Your flowering encyclopedic mind

One fertile shrub which unbeknown to you

Can dull the pain of labouring womankind.

Below the crest of this Elysian Mount

Among the emerald fields of Spileos,

A flower in a crinkly velvet gown,

Lies blushing pink atop a bed of moss.

Within the textured folds of its embrace

Flow limpid springs of blissful pain-relief

More mellowing than any lotus fruit,

More potent than a eucalyptus leaf.

Pluck its petals, pulverize, infuse,

Then rally the midwives of labouring Greece,

Let Hermes wing his sandals with the news:

“Tears in childbirth evermore shall cease!”’

Up starts the youthful healer of the gods

And breaks into a Myrmidinian run

Like hope unfettered from Pandora’s box

Fleet-footed in the rosy-fingered dawn

On Mount Olympus Paeon’s footsteps flow

Past purple debutante and wild sage,

Spring gentiana – queen of alpine plants –

Pale lilacbush and silver saxifrage.

Through prostrate speedwell Paeon carves a way,

Heeds not the colonies of coralroot

Nor jankaea rosettes of felted grey

Nor tiger orchids trampled underfoot.

To wintergreen and Greek fritillary

Swift Paeon does not give the time of day

But reaching Spileos, Beauty stops him short

A bough of French lime blossom bars his way.

Prodigious Paeon shuts his eyes and breathes

That subtly tantalizing citric smell

whose loveliness is vividly inferred

from memories of Loveliness herself.

And where else must his anaesthetic grow

But in the shadows of this sensuous tree.

The herbalist entreats the silken-haired

High queen of all things hidden, ‘Help me see!’

Delight comes on his heart, and looking down

Asclepius’s apprentice comes across

Ten flowers wearing crinkly velvet gowns

And blushing pink atop their beds of moss.

Young Paeon plucks a bloom and holds it high:

‘I name this veiled treasure Paeony,

I dedicate it to the bride of Zeus,

To motherhood and femininity!’

The Traveller

~ 1 ~

The sun burns orange in the western sky,

It dips and disappears, and way up there

On old Yakuuba’s toothbrush tree you sigh

A sweetly sorrowful pre-migration prayer.

You launch into the void in search of spring,

Whatever doesn’t kill you makes you strong.

A vulture shrugs a valedictory wing:

Au revoir, mon beau phragmite des joncs!

~ 2 ~

Your beak’s magnetic compass does not work

In equatorial lands, but warbler eyes

Are bright, Polaris too, and in the circle

Of Cassiopeia’s spinning throne you’ll find

Your circumpolar south and shining north.

Unflappable at fifteen hundred feet

You flap the lonely trans-saharan course.

Assalaam alaikum, dsaysie.

~ 3 ~

Second right at the dunes of Bouffadi

And straight on till morning you fly,

How weary this passerine passage,

How wind-glazed your warbler eye.

Approaching Tammi you slow down, amazed

By apricot and date palm potpourri,

A heaven-sent pit stop oasis,

Alhamdulillah, dsaysie!

~ 4 ~

For three days at Tammi you refuel your tank

With dainty dates and pomegranate juice,

You know al Jenna is no breeding bank,

You have to bid goodbye, break loose

And set your beak like flint toward the north,

So callibrate your hippocampus compass

To navigate the harsh Mahgrebi course.

Wa alaikum assalam, dsaysie.

~ 5 ~

I ♥ Atlas mountains, I ♥ Alboran Sea,

I ♥ Ibiza, I ♥ Tombouctou,

You’ve been there, flown that, got all the T-

shirts and the yellow jersey too.

Bleary-eyed and weary-winged, you arrive

In the Balearics not one flap too soon

And light on an Aleppo pine – alive!

Bienvenido, carricerín común.

~ 6 ~

One day lying zonked in a carob tree,

Two more in a lethean almond grove,

But now your Devonian destiny

Revives you for the anchor leg above.

With pitiful heaves of feathery flanks

You ride with a heavenly Tour de France,

Match aching wing-beats with the avian ranks,

Allez-allez, petit phragmite des joncs!

~ 7 ~

There’s no Olympic lane on your commute,

No level crossing, toll or traffic isle.

You’ve no congestion charges to compute,

Just geodetic azimuths and miles.

You toil across La Manche and in

The distance spy a Union Jack

And then a holly hedge and wheelie bin.

Hello, sedge warbler, welcome back.