I created Tegla Books to bring my stories to readers everywhere, and to honour my great-grandfather E. Tegla Davies, a beloved children’s author in Wales. Visiting his old haunts in Llandegla, Bangor, and Tregarth recently gave me a fresh appreciation for his life and his stories, which were full of humour and mischief.

The Tegla Books logo, a letter T woven with a traditional Welsh knot, celebrates that heritage. It’s about connection, continuity, and discovering something rooted in the past that still feels alive today.

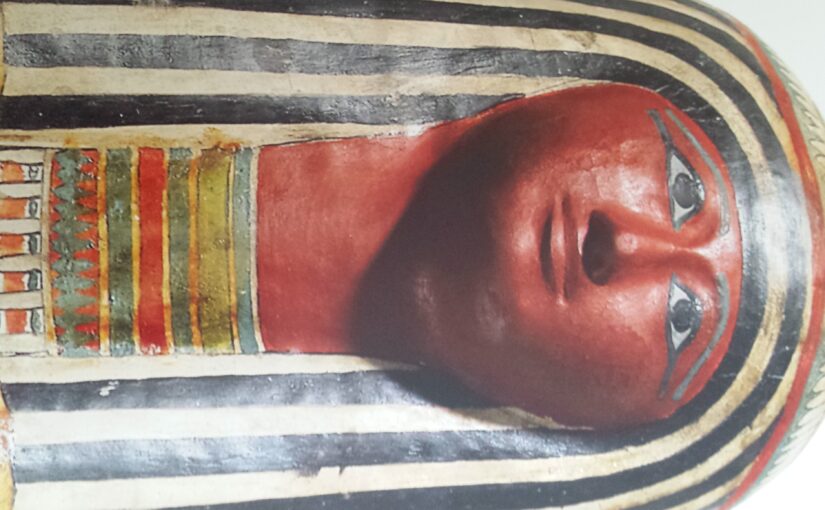

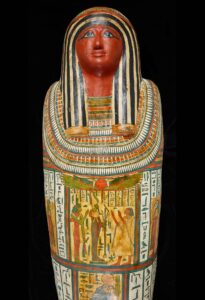

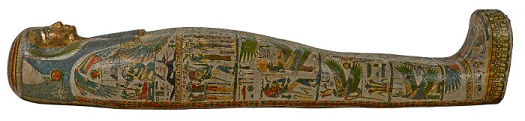

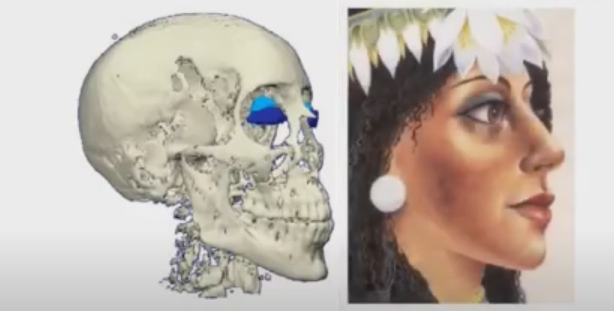

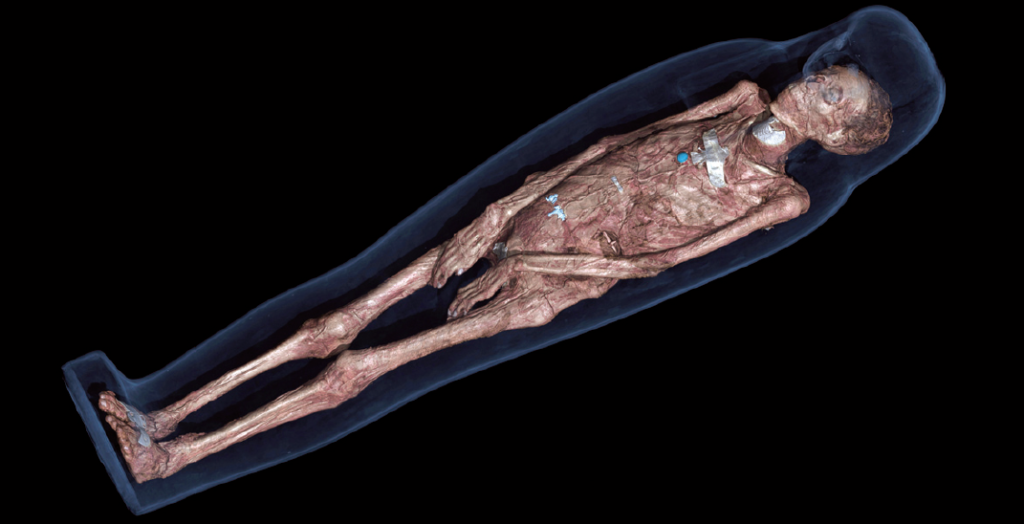

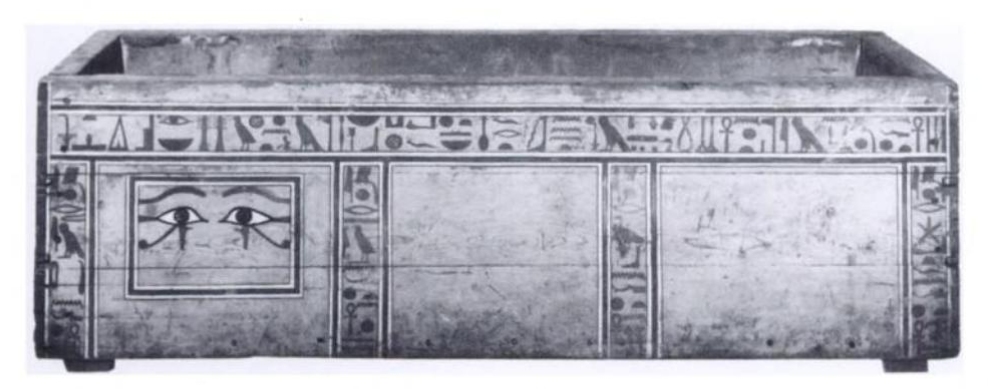

The first novel under the Tegla Books imprint is HOW TO STEAL THE ROSETTA STONE, a Young Adult heist adventure published on 9 October 2025. Set in London, it follows a group of clever, resourceful teens from an international school in Egypt as they attempt to repatriate the famous Rosetta Stone to its land of origin. As a lifelong fan of the heist genre, I loved writing this book, and I’m really hoping it will be well received.

Tegla Books is where stories with heart, heritage, and suspense come together, and I can’t wait for you to experience them.